Month: December 2015

I vote in the Village Voice Pazz and Jop Poll Again

Above are my choices for Top 10 albums and singles for 2015 (ignore what I thought were my Top 10 albums, below). In addition to being invited to submit a ballot (100 points distributed among 10 albums, no fewer than five points, no more than 30, per rekkid), we can mail in an essay or more scattered “commentary,” which is usually all I have time to do. For those on tenterhooks, here is my attempt to put shit together in a world of chaos!

“If a year-end best-of-pop-music Top 10 lacks the presence of anyone 70 or older, it’s lying. As has been proved over and over again, though pop was, perhaps, once actually a youth music, the older guys (and gals) not only know what it’s all about, but they really have it all worked out. I think Gram Parsons sang that. Just before he died at 26.

Though my Top 10 has more fresh blood than maybe any ballot I’ve ever submitted—Courtney Barnett is absolutely irresistible, the comparatively ancient Kendrick Lamar an irrepressible force whose growing confidence I hope isn’t dulled by pessimism—it’s got plenty hair sprouting out its ears. Made in Chicago: Muhal Richard Abrams 85, Roscoe Mitchell 75, headliner Jack DeJohnette 73, Henry Threadgill the pup at 71, all celebrating the AACM’s 50th anniversary—and not with a bingo game. Welcome Back: Irene Schweizer, 74, and Han The Man Bennink, 73, joining forces to improvise racket and rhythm into beauty once again after two decades. Albert Ayler’s Ghosts Live at The Yellow Ghetto: John D. Morton, 62, and Craig Bell, 63, proving that a very bad attitude, ugly noise, and irreverence aren’t the exclusive property of the kids—and also pushing siblings Willie Nelson, 83, and Bobbie Nelson, 84, to #11 and off the ballot. I feel a little guilty about that decision—but Willie shouldn’t have recycled so many songs. This is serious business.

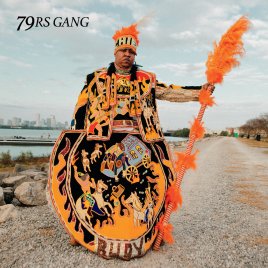

Really, though, looking at my list, it isn’t mostly about age. It’s about time and race. Between the 1885 formation in New Orleans of the first “black Indians gang,” The Creole Wild West, and the hands-across-the-‘hoods of the 79rs Gang’s Fire on the Bayou, on which New Orleans’ 7th Ward Creole Hunters and 9th Ward Hunters team up on a rare stripped-down Mardi Gras Indians record, lay 130 years of self-defense and self-preserving “social clubs” that shouldn’t still be necessary.

Between the first Chicago meeting, in 1965, of a group of young musicians debating the laws and details of an impregnable artistic sanctuary and classroom called the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (its first record, Sound, by Mr. Mitchell, arrived in ‘66), and Made in Chicago’s defiant proof of the founders’ and the organization’s undiminished power stand cultural, financial, political, and aesthetic obstacles Hercules would have been hard pressed to surmount.

Between Alex Haley’s “faction” of an 18th century Kunta Kinte and Mr. Lamar’s “King Kunta” testify 250-plus years of deliberate oppression that shape-shifts with every hard-earned challenge. Maybe you’d argue that this isn’t how I should put a year-end best-of-pop-music Top 10 together. I’d counter that the records are that good, and they may be that good because of what sprawls across the expanse of time and presents itself to us right now. Or maybe not.

Some further notes about time and race: Jeffrey Lewis’ Manhattan-leading “Scowling Crackhead Ian”’s persona wearily and compassionately peers back across the years—all the way to grade-school horrors perpetrated by a human he stills sees regularly, 20-some years later. He wonders when the two of them can just…shake hands and put the past aside. That was the most moving line I heard all year, and I couldn’t help but hear it, too, as a metaphor for our country’s own near-fatal stubbornness. And Allen “The Maine Monk” Lowe’s mournful, angry, questioning jazz march “Theme for the Nine (Murdered in Church, Parts 1 & 2)”—smeared with the haunting blues baritone of Black Artists’ Group founder Hamiet Bluiett, 75 years young himself—was the first serious musical response to the Charleston massacre. Have there been others? I don’t know. But I expect them.

The best thing about listening to the music I liked most in 2015 was that it forced me to wonder whether we are capable of the change we need to make, and question myself about whether I have been doing enough to make that change happen. Also—I will be honest— whether I even want to be part of this continuing social experiment that refuses to unmask itself, for its own good. Time and race—I can’t get them off my mind.”

The lucky blatherers get either a few sentences or, in select cases, whole essays excerpted in the corrupted old Village Voice itself. I’ve been excerpted four times, and this strange offering is not likely to get published fully. But it’s fun to try. And I really believe it: pop music is youth music, but way more–it’s an avenue for old farts to pass along wisdom as to what to expect! Aren’t you interested?

Some of my favorite “singles” for 2015:

My Official 2015 Top 20 Rekkids

In another post below, I listed 116 discs from 2015 that I thought were plenty good. Should you have cared, just reading it might have seemed daunting balanced against trying to properly live your life. For folks with less time on their hands, here is the Top 20 I’m going to send in to the various polls to which I am asked to contribute, followed by my favorite 15 “archival digs”–collections of old stuff that demands reconsideration, but shouldn’t properly take up space on a REAL EOY Top 20.

- Jack DeJohnette: Made in Chicago (ECM)

- Kendrick Lamar: to pimp a butterfly (Aftermath)

- Jeffrey Lewis & Los Bolts: Manhattan (Rough Trade)

- Courtney Barnett: Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit (Mom & Pop)

- John Kruth: The Drunken Wind of Life—The Poem/Songs of Tin Ujevic (Smiling Fez)

- Irene Schweizer, and Han Bennink: Welcome Back (Intakt)

- 79rs Gang: Fire on the Bayou (Sinking City)

- Africa Express: Terry Riley’s “In C”—Mali (Transgressive)

- Willie Nelson and Sister Bobbie: December Day (Legacy)

- Allen Lowe with Hamiet Bluiett: We Will Gather When We Gather (self-released)

- x_x: Albert Ayler’s Ghosts Live at the Yellow Ghetto (Smog Veil)

- Coneheads: P. aka “14 Year Old High School PC–Fascist Hype Lords Rip Off Devo for the Sake of Extorting $$$ from Helpless Impressionable Midwestern Internet Peoplepunks L.P.” (Erste Theke Tontraeger)

- J. D. Allen: Graffiti (Savant)

- Nots: We Are Nots (Goner)

- Los Lobos: Gates of Gold (429)

- Heems: Eat Pray Thug (Megaforce)

- Erykah Badu: But You Cain’t Use My Phone (self-released)

- Songhoy Blues: Music in Exile (Atlantic)

- Drive-By Truckers: It’s Great to Be Alive! (ATO)

- Wreckless Eric: AMEricA (Fire)

Top 15 Archival Digs or Comps

- Bobby Rush: Chicken Heads—A 50-Year History(Omnivore)

- The Velvet Underground: The Complete Matrix Tapes (Polygram)

- Continental Drifters: Drifting—In the Beginning and Beyond (Omnivore)

- Various Artists: Ork Records–New York, New York (Numero)

- Jerry McGill: AKA Jerry McGill (CD) + Very Extremely Dangerous (DVD) (Fat Possum)

- Dead Moon: Live at Satyricon (Voodoo Doughnut)

- Various Artists: The Year of Jubilo (Old Hat)

- Various Artists: Beale Street Saturday Night (Omnivore)

- Various Artists: Burn, Rubber City, Burn (Soul Jazz)

- Sun Ra: To Those of Earth…and Other Worlds–Gilles Peterson Presents Sun Ra And His Arkestra (Strut)

- Bob Marley & The Wailers: Easy Skankin’ in Boston, 1978 (Tuff Gong)

- The Falcons: The World’s First Soul Group—The Complete Recordings (History of Soul)

- J. B. Smith: No More Good Time in the World For Me (Dust-To-Digital)

- Ata Kak: Obaa Sima (Awesome Tapes from Africa)

- Reactionaries: 1979 (Water Under the Bridge)

The Violence of Chuck Berry

(The following is an excerpt from a memoir I am writing about my career in public education. Music had a lot to do with it, believe me.)

I have taught many unusual lessons in my career. This one was not only successful (though even the best lessons are only partially so), but its history also incorporated a lot of the best and not a little of the worst of this profession.

I was teaching middle school at the time and was graced with a bunch of seventh graders who were game for anything interesting I proposed. They would go on to make me look great many, many times that year. In this case, their lesson grew out of a screw-up on my part.

Striving to realize our school’s challenging goal of integrating curriculum, our instructional team had tried to design an opening unit focusing on the idea of “culture.” For three weeks, each teacher—math, science, social studies, reading, writing, and special education—would design his or her instruction so that it addressed that common theme, with the unit output being a single assessment of learning, as opposed to five separate tests. Theoretically, it still sounds neat to me—in fact, it drew me away from my previous job just for the chance to try it. In reality, it’s a bitch to pull off. Just trying to talk about it caused my first teaching team to implode.

At this point in my middle school tenure, however, I was surrounded with comrades willing to give the idea a shot. We planned our culture unit very meticulously, and, of course, I, likely the most enthusiastic among us, zipped through my part of the unit quicker than necessary, quite possibly leaving a few students in the dust in the process. So, confronted with an additional three lessons to write before my fellow teachers were finished, I decided to give the young’uns a dose of Missouri culture and rock and roll, as well as an opportunity to be creative.

I have often said, only half-joking, that I teach to subsidize my record collection. But I have always reinvested what I’ve gained from music in the stock of U. S. public schools’ pop culture curriculum (even though that exists only in my mind), and, in this case, I thought it would be valuable for my students to study how one great rock and roll writer reflected his rich and complicated culture. I prepared, with one eye on Fair Use guidelines, a handout highlighting some of Mr. Chuck Berry’s most revealing lyrics (“Brown-Eyed Handsome Man,” “Too Much Monkey Business,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” and “Back in the U.S.A.” among them), prefaced the lyrics with a quick artist bio, then guided the class through some close-listening of his music. As we proceeded, I led the kids in discussing what we had learned about U. S. culture circa 1955-1964, and advised them in taking a few notes. Then, over the next two periods, we put our shoulders to the wheel of the task: either write a song of your own, reflecting current U. S. culture, in Chuck’s style, or write a song about Chuck’s version of U. S. culture in your own style.

We had a blast, and, I must say, their work was very perceptive, witty, and—what do you know?—indicative of their having learned some valuable things! A couple students even brought guitars and played their songs. What we’d done leaked outside of our classroom (not surprising, in that my classroom was open to the hallways!), and we soon learned that our homeschool communicator’s college roommate had been Chuck’s lawyer at one point—and had his phone number.

One of the kids excitedly blurted, “Hey! Let’s send Chuck some of our songs!” You don’t say no to such a proposition, and soon the ex-roomie lawyer was on the horn to Chuck, asking him if he’d be up for reading some 7th graders’ tribute-songs to his bad self. Almost immediately, we received word back from Berry: send them on! We did a quick read-around, whittled our stack of 150 songs down to the best 30—we didn’t want to swamp ol’ Johnnie B. Goode!—slid them into a “vanilla envelope,” and put ‘em in the post. I didn’t really expect to hear from Chuck again; one of my long-time philosophies regarding ambitious enterprises is to expect absolutely nothing, which intensifies the exultation if things work out.

The next thing that happened was not a working-out.

A week after the culture unit’s conclusion—it worked nicely, but we were never to replicate its success beyond squeezing a birds-and-the-bees discussion into a “plant life cycles” unit—came our school’s “Back to School Night,” a late summer public ed staple during which parents are invited to meet their students’ teachers. These evenings usually prove a bit of a dog-and-pony show on our parts, but they are seldom high intensity, and, though the parents who most need to come don’t (usually they can’t—they are working), we usually at least mildly enjoy the opportunity to communicate to the grown-ups what we’re up to.

I didn’t expect to be called to the principal’s office. Via intercom.

When I stepped into her office, in front of Dr. Brown’s desk sat what I presumed to be a parent. On the parent’s lap lay her daughter’s English folder, open, with the Chuck Berry handout removed and unmistakably on display. I thought, “Oh shit—she’s a journalism professor and she’s got a copyright complaint. I knew I should have picked up those handouts after we finished writing!” I stood at attention, ready to be, perhaps justly, upbraided.

“This man does not have the moral fiber to be teaching my daughter!”

I take copyright seriously, but, well—wasn’t that a bit strong?

But this wasn’t about copyright. I could not have possibly guessed what it was about.

Remember that “quick artist bio”? I know what you’re thinking: no, I did not mention Chuck’s Mann Act scrape and accompanying prison stint, nor his naked photos with equally naked groupies, nor his tax evasion escapade, nor his exploits with video technology. Nor did this mother look those biographical tidbits up. (All idols have feet of clay, anyway.) Her concern was this: I was promoting violence in this unit.

She said that. Yes. And it was in the bio ‘graph I had written, branded into my memory since:“Berry’s machine-gun lyric delivery in songs such as ‘Too Much Monkey Business’ (see below) influenced none other than Bob Dylan, one of this century’s greatest songwriters.” She read that aloud, from the handout, to my principal and me, with supreme confidence and righteous indignation, as if it were irrefutable proof I was a warlock.

Wait—what??

Actually, I think that is exactly what I said. I looked at Dr. Brown—an excellent administrator I had purposely followed over to this particular school, and a human whom I was desperately hoping valued loyalty at the highest level—and stared in disbelief. The mother stood, read the passage aloud again, and punctuated it with this outburst: “It says right here—‘machine-gun lyrics’!!!” (As you can see above, it didn’t quite say that.)

I confess to being a lifelong smartass, but my reply was simply self-defense: “Do you understand figurative language?”

“Don’t try to slither out of this!” At that moment, I was the closest I have ever been to deeply understanding Kafka. And “slither”? Really?

Keeping my far eye pleading with the principal and my near one defiantly on my judge, I patiently explained the point behind the lesson. No sale.

I looked directly at my boss and said, in quizzical defeat, “Well, you could move her daughter to another team.”

The parent exploded. “She’s not going anywhere!”

I was stunned. I reflected for about an eighth of a second and said, to them both, “This is ludicrous. I have sane parents to speak to. Do what you must. I cannot explain more clearly what my valid and very moral intentions were. Goodbye.” Turned on my heel, went back to my class, and pictured two die spinning through the air.

That absolutely wonderful administrator, Dr. Wanda Brown, refused to budge in giving me full support—that’s one of the reasons why she still hangs the moon for me. The parent pulled her daughter from regular classes for homeschooling (I am sure, much to the daughter’s embarrassment), though she continued to send her over to us in the afternoon for French classes (that’s bullshit, if you ask me—you teach her French, lady). In spite of the whackiest—and wackest—parental guidance episode I had ever witnessed in my career, I proceeded to have a better year than Frank Sinatra’s in the song. The story of the Chuck Berry unit, however, had not yet concluded.

Spring. That lovable homeschool communicator rolled into my classroom—he did, in fact, roll—and motioned me over.

“Chuck’s coming to play at a local high school next week. [He lives in Wentzville, Missouri, just down I-70 from Columbia.] He loved the packet of songs, and he’s authorized you to bring over the ten student writers you think would get the most out of hearing and meeting him. I’ll take care of the bus.”

As the generation of teachers prior to mine would have exclaimed, “My goodness!” (That is not what I said; I repeated the title of a well-known Funkadelic title exclamation, but my moral fiber is too strong to repeat it here.) Though selecting the ten students proved an exercise in pure agony, we were soon filing into the choir room of the local high school, where the kids were given a front-row seat—

a mere five feet from the man himself, at that moment swiveling on a stool, his guitar on his lap.

My natural high was so intense, I cannot remember much of Berry’s talk, other than that Chuck gave rap lyrics his seal of approval (good man, and my kids beamed). However, when the afternoon turned to Q&A, I received an electric charge greater than a cattle prod’s when one of my students, Sekou Gaidi (whom I must name for posterity’s sake), stood to ask a question. Sekou, who often underperformed for me despite frequently being the smartest person in the room (including me), had actually been inspired during the Chuck Berry unit and written a killer song. He was also a combination of a cannon packed a shade too loose and Sun Ra (a jazz genius who uttered many a head-scratcher in his day). I admit, as the charge passed through me, that I was holding my breath.

Chuck: “Young man, what would you like to ask?”

Sekou: “I don’t know who in the heck you are”—Unadulterated claptrap! He was laser-focused through the entire three-day lesson!—“but my mom wants you to autograph this book.”

This request was delivered dry as toast, with arm toward the stage, Chuck’s recent autobiography at its fingers’ end as if it were trash recently plucked off the ground. Sekou’s expression? Slot-mouthed.

Three beats of silence. Excuse me while I break to present tense.

Chuck—Chuck Berry—is staring (glaring? I couldn’t tell!) at Sekou, then a pudgy, bespectacled little seventh-grader wearing mauve sweats. I am covering my hands, shaking my head, fairly sure that this is one of Sekou’s jokes, stunned by his unholy audacity if I am correct, and dreading what might rush into the resulting vacuum of silence.

Into the void rush explosive guffaws, straight out of the gut of The King of Rock and Roll. Then out of the audience’s. Then out of mine. My team teacher is laughing so hard she’s tearing up, and my wife Nicole, who’d come along and would later get her own copy autographed, is staring at me in stunned, gaping delight. In fact, I am tearing up a little right now, staring at this screen, mouth agape as I recall it.

Thus properly ends one of the best lessons I ever taught, embedded in the history of which, as with all the best lessons, are other very important lessons. I can only be thankful that the lessons did not come at me with machine-gun-like rapidity.

Folk-Funk Comes to Hickman High School!

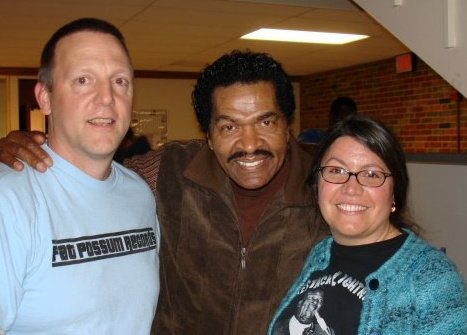

Bobby Rush signs student autographs after his show in Hickman High School’s Little Theater. (Photo by Notley Hawkins)

(This piece is part of a memoir-in-progress about my 30+-years of high school edumacating that may or may not appear some day in completed form.)

Sometimes great things fall into your lap, and you have to be ready for them.

In 2009, my wife and I had just returned from a trip to Memphis, and on the way down and back, we’d listened to a heap of Bobby Rush tracks. Bobby, a native of Homer, Louisiana, is the inventor of what he calls “folk funk”: music too funky for blues, too bluesy for funk, and designed for very down-to-earth people. He has also been incredibly durable. One could argue that not only his recordings but also his performances are more vital now than they were thirty years ago; currently in his eighties as of this writing, he shows no signs of slowing down. We’d barely unpacked when my phone rang. The caller was an associate of the Missouri Arts Council, and she’d gotten my name from an acquaintance who’d mentioned that I’d arranged rock and roll concerts at my high school.

“Would Hickman be interested in hosting a blues artist for a concert next month?”

That would seem to be a no-brainer, but as fans of the graphic novel and film Ghost World know, the wrong band or artist can give an audience the blues rather than relieve it of them. I wasn’t going to be held accountable for a Blueshammer-styled band, nor, I must be honest, a painfully sincere “bloozeman” of any stripe. Thus, I had to put on the brakes.

“Well, it depends upon whom. When we do these things, we like to do ‘em up all the way, and I’d hate to, you know, do up something anti-climactic.”

“Have you heard of Bobby Rush?”

I didn’t know whether to shit twice or die.

“Can you hear me ok?”

“Yeah, sorry, I was just a little overcome there. Hell, yes, we’ll do it! Give me the details!” Usually, I asked for the details before agreeing, but, in this case, I would have been a fool.

“Well,” she said, “It’s free of charge to you and the audience; a grant’s paid for it. Bobby’s got his own band and gear—you’d just need to provide a basic PA and monitors. And we’d like to schedule it for the evening so kids could bring their families if they wanted to. I tried to pitch this to Jefferson City Public Schools, but they wanted nothing to do with it.”

“You snooze, you lose. And this will be a huge loss for them. We’re A-OK on the equipment. And evening is great. But, regarding the kids and their families—is Bobby bringing the girls?”

I am sure this is a question anyone trying to book Rush is going to get asked. Bobby frequently performs with three triple-mega-bootylicious dancers to whom he often makes leering but strangely warm and charming reference throughout his shows, and a) I seriously hoped he was travelling with them, but b) I wasn’t sure the snug stage had room for them, and c) I was not sure a transition from high school performance stage to chitlin’ circuit showcase would be altogether without bumps (take that as you will).

She chuckled. “Oh no, he doesn’t have the girls on this leg.” I breathed a sigh of disappointed relief, as well as applied a mental Bobby Rush-like chuckle of lechery to her phrasing.

The next day, the kids of the Academy of Rock, our music appreciation club, and I revved into PR gear. We made and posted flyers, we networked the hallways and school nooks and crannies, and we set up visits to the American history classes, where we planned to show a brief “teaser” segment on Rush from Richard Pearce’s “The Road to Memphis,” an installment of Martin Scorsese’s The Blues series. Because I have been a serious nut about music since I heard “Then Came You” float out of a swimming pool jukebox, I have always been careful to find a solid justification for connecting any school use of it to curriculum—probably too careful, but I am like a Pentecostal preacher when I get going, and may the Devil take the curriculum. In this case, the justification too had fallen into my lap: it happened to be Black History Month, and, as dubious as I consider the concept (I prefer Black History Year), I was happy to exploit it. I was also happy that, in my long experience at Hickman, I’d seldom seen a major event staged that directly and intentionally appealed to our 25% black population. Not that I could take credit for anything but saying “yes” to the proposal; in fact, that could accurately serve as my epitaph: “He said ‘Yes’ to life.”

We also got word out to the local press—who were underwhelmed as usual, for the most part—and the Columbia music community, which resulted in my fellow music maniac Kevin Walsh and his young pal Chase Thompson showing up to make a film—as yet unreleased, but I have a dub—of Rush’s appearance.

The day of the show seemed to arrive in an instant. We promptly set up the stage and PA—but, for some reason, the monitors, not exactly top of the gear list in complexity of use, were malfunctioning. We tried everything we knew (admittedly, not much), to no avail. At least we had a computer properly jacked into the PA to record the show, which Bobby’d happily agreed to let us do. Still—one of the few things we’d been asked for we couldn’t deliver. I was also nervous about the turnout, as we had no way of knowing how many folks would arrive, since admission was free.

Bobby and his band (also known as the crew—they hauled and set up their own equipment, which is no unremarkable habit, especially for road vets) arrived right on schedule, and, after finding him and introducing myself and my wife Nicole, I cut right to the chase: “Bobby, our monitors are screwed. That’s about all you wanted, and we messed it up.”

“Phil, Bobby Rush got this! You OK! Been on the road for sixty years and ain’t nothin’ like that ever stopped us! You all just sit back and relax and let Bobby Rush take care of business.”

I couldn’t argue with that. Would you have?

We did as we were told and took a seat. The space was an old-style “Little Theater,” capacity 150, with nice track lighting, comfortable seating, and just enough stage for a five-piece band (Bobby had seven). I am assuming it was originally built for student theatrical performances, but, in the ‘Oughts, it was just as frequently a concert venue. As I write, I feel a pang of sadness in not being there to continue using it.

Bobby and his band genially integrated our small crew of students into their own set-up and soundcheck—they’d also quickly jerry-rigged the monitors and had them working—and were thrilled to find that we planned to have one of the kids run sound for the show. This had been our philosophy since the club was formed in 2004: move over and let some students do the popcorn! An element of risk always threatened proceedings as a result, but that’s life, learning happened, and it’s more fun riding on The Wall of Death, anyway.

I had been in a bit of a nervous trance when I suddenly broke it, looked around, and noticed that the house was almost packed. Not only that, but the concertgoers were predominantly black—with a considerable number of parents and grandparents among them. As is my wont, I quickly twisted my joy into worry as I began to recall certain bawdy Rush routines that might be revisited that very eve.

I needn’t have worried. Bobby Rush had this. 75 at the time, he must have set the record for pelvic thrusts in one show. The crowd went wild. He told raunchy stories, including one featuring his minister father. The crowd hollered. He plum-picked his sly repertoire: “Uncle Esau,” “I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya,” “I Got Three Problems,” “Henpecked” (“I ain’t henpecked!/I just been pecked by the right hen!”), “Night Fishin’,” “Evil,” “What’s Good for the Goose.” The crowd exploded. He produced a pair of size-75 women’s undies to demonstrate his taste in derrieres. The crowd went bonkers, and the grandmas stood up and shouted amen. He accused our sound man of being a virgin. The crowd—and our soundman—went nuts. He talked about visiting Iraq, about his prison ministry, about struggling up out of the Great Migration to Chicago, about being on damn near every black music scene for fifty years—and about coming through it all to vote for a black president who actually got elected. And the crowd hung, hushed, on his every word, as he delivered a brilliant, deeply personal history lesson we hadn’t even asked for. Even the jerry-rigged sound in that little room was hot as fire and deep as a well, with Rush playing harp like he was possessed by the ghost of Sonny Boy Williamson and snatching a guitar away from a band member to play some razor-sharp solo slide. As I continued to nervously scan what had become a congregation, I was thrilled to notice that the older the person was whom I spied, the wider his (or most definitely her) grin was. The students? They had clearly never seen anything like Bobby Rush before. Our soundman was so mesmerized he forgot to check the recording levels, so our aural document of the show is way into the red.

I know it’s a cliché, but it was, for damn sure, a religious experience. The audience, I think, was more drained than Bobby at show’s end, but not too drained to be shaking their heads in wonderment and giggling with glee. Several of those older folks swung by to tell me, “More of this, please!” The principal who’d drawn event supervision—lucky man!—asked me, “How in hell did this happen, and when’s the next one, ‘cause I’m calling dibs?” Of course, I’d liked to have met those demands with serious supply—but witnessing a bona fide, down and dirty, authentic-but-for-the-booze-smoke-and-BBQ chitlin’ circuit show at a Bible Belt high school, I’m afraid, is a once in a lifetime experience. God, I do love grants and art councils.

Nicole and I walked Bobby out into the February night, his arms around both of our shoulders. His eyes and jeri curls were shining, but he hadn’t seemed to have broken a sweat. “I want to thank you all for having us,” he offered, humbly. “I don’t know who had more fun, us or them!”

I quickly replied, “No, man, thank you! That show was so good you’d think you were playing for the president! And we’re just a high school in Missouri!”

He shook his head, smiling.

“I told you, Phil…Bobby Rush got this!”

See Columbia photographer Notley Hawkins’ classic shots from the show here, and do yourself a solid and grab Omnivore Records’ stellar four-CD career summation of Rush, Chicken Heads, here!